From time to time we bring you the quirky side of neuroscience here at BrainEthics. Now, we discover a funny little study in Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging that bears the attractive title “The neural basis of unconditional love” by Mario Beauregard et al. Indeed, the study of the neural bases of preference formation, aesthetics and even love have gained much momentum since this field started just a few years ago. Fields such as neuroaesthetics and neuroeconomics seem to overlap when it comes to these studies, in which the core aim is to study the fundamental processes underlying preference formation.

From time to time we bring you the quirky side of neuroscience here at BrainEthics. Now, we discover a funny little study in Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging that bears the attractive title “The neural basis of unconditional love” by Mario Beauregard et al. Indeed, the study of the neural bases of preference formation, aesthetics and even love have gained much momentum since this field started just a few years ago. Fields such as neuroaesthetics and neuroeconomics seem to overlap when it comes to these studies, in which the core aim is to study the fundamental processes underlying preference formation.

In the study, Beauregard and colleagues wanted to establish the neural bases of unconditioned love. So the first tricky thing would be to define and operationalise what is meant by “unconditioned love”. IMO, such kind of love is the affectionate feelings one would call religious love, or ultimate altruism…(if such ever exists).But following the name, it does suggest a broader definition of affectionate feelings towards a person (or just any thing?) regardless of their origin, persona, deeds or misdeeds, family bonds and so forth.

Claimed amygdala deactivation during maternal love, which rather looks like collateral sulcus/entorhinal cortex... (from Bartels & Zeki 2004)

Similar studies of strong affectional feelings to other persons have been conducted recently. For example, in a study of maternal love (PDF) by Bartels and Zeki, mothers were scanned while looking at baby faces, in which sometimes their own newborn’s face was shown. The researchers found that when looking at their own babies, compared to looking at other infants, mothers demonstrated stronger activation in regions such as the ventral striatum/nucleus accumbens, ventro-anterior cungulate cortex and fusiform cortex.

In addition, and to the researchers’ surprise, they also found stronger bilateral activation of the anterior insula, a structure typically involved in aversive functions (but I will not follow the speculative account of the researchers on this activation). Deactivations were claimed to be found in regions such as the amygdala – which really is not amygdala, but rather collateral sulcus, judging from their figure (see figure on right). Isn’t is strange that prominent researchers such as Semir Zeki goes so wrong in neuroanatomy? The consequences from arguing for deactivation in the entorhinal cortex, compared to the amygdala, is dramatic. Instead of talking about emotions, one would be more prone to talk about complex visual processing. Yes, it does matter where you think your blobs are…

So what did Beauregard and colleagues do differently? First, they needed to describe the uncondition love construct, which they describe as:

(…) distinct from the empathy and compassion constructs. Empathy is commonly defined as an affective response that stems from the apprehension of another’s emotional state (e.g., sadness, happiness, pain), and which is comparable to what the other person is feeling (Eisenberg, 2000). This affective response is not unconditional and does not involve feelings of love. Compassion refers to an awareness of the suffering of another coupled with the desire to alleviate that suffering (Steffen and Masters, 2005). In contrast to compassion, unconditional love is not specifically associated with suffering.

Hm, not a particularly good definition to go hunting for neural correlates to. Nevertheless, the aim was to study the neural basis of unconditional love, something that has not been done before. So how did they do it? First, the authors had to select the subjects:

Participants were assistants in two l’Arche communities located in the Montreal area. L’Arche communities (founded by Jean Vanier in 1964) are places where those with intellectual disabilities, called core members, and those who share life with them, called assistants, live together. This special population was selected on the basis that one of the most important criteria to become an assistant is the capacity to love unconditionally. (We recruited) assistants with a very high capacity for unconditional love. We ensured that all recruited individuals understood the meaning of this form of love (based on the construct presented in Section 1) and found their work at l’Arche (community help service) very gratifying.

The hypotheses were 1) unconditional love is rewarding, and therefore it was expected to be associated with activation of the VTA and dorsal

striatal regions; and 2) since unconditional love experientially differs to a large extent from romantic love and maternal love, it was predicted that this form of love would be mediated by brain regions not involved in romantic love and maternal love. I particularly hate this second hypothesis: it’s not really a hypothesis, because ANY activation that is “different” can confirm this hypothesis. If it’s a fishing trip, let us know…

Let me try a bit of further deconstructionism of this study. In the methods section, it is described how the subjects were instructed to look at unfamiliar faces and either attempt to feel unconditioned love or think about the person’s intellectual capacity (sic.).

A blocked-design was used to examine brain activity during a passive viewing (PV) condition (control task) and an unconditional love (UL) condition (experimental task).

Note: using block designs are typically used to study differences in state (e.g. comparing neural activation during different attentional states).

Five blocks of pictures were presented during both conditions. Each block consisted of a series of four pictures. Each picture was presented during 9 s (pre-experimentation revealed that, on average, participants needed that long to feel unconditional love toward the individuals depicted in the pictures).

OK, so some of the activation differences between the UL condition and the PV condition may be due to task difficulty and reaction time, and not, as they would have wanted, the nature of the task.

Blocks were separated by periods of 30 s. Pictures depicted individuals (children and adults) with intellectual disabilities. These individuals were unfamiliar to the participants. Instructional cue words (“View”, “Unconditional love”) printed in white first appeared in the center of a black screen for 2 s. While the picture remained on the screen, participants performed the tasks specified by the prior cue. In the PV blocks, participants were instructed to simply look at the individuals depicted in the pictures. In the UL blocks, participants were instructed to self-generate a feeling of unconditional love toward the individuals depicted in the pictures.

OK, there are many assumptions here… Just to illustrate, do the following for me: close your eyes and for 20 seconds DO NOT THINK ABOUT AN ELEPHANT!!! What happens? Well, you’d probably be surprised to see that elephant does really appear in your mind even if you try to suppress it. Thought suppression studies have demonstrated this through the past many decades. So IMO, what the study might also be about is thought suppression – or comparing elephant thinking to elephant-suppression activation. IOW, I’m not sure that the viewing condition did not evoke some “unconditioned love”-suppression.

Therefore, the UL task involved both a cognitive component (self-generation) and an emotional–experiential component (feeling). Blocks were presented in alternation (PV, UL, PV, UL, etc.). At the end of each block for both experimental conditions, a four-point scale (1 = “No feeling”, 2 = “Some feeling”, 3 = “Moderate”, 4 = “Very intense”) for rating the extent to which they currently felt unconditional love was presented for 3 s.

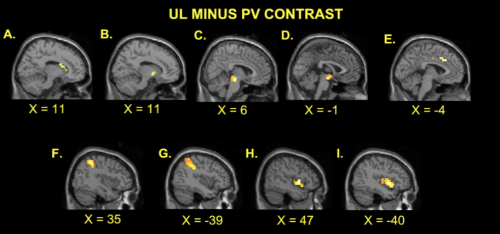

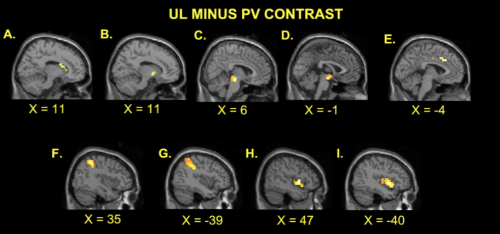

Strangely, what the researchers found when doing the UL minus PV comparison, was stronger activation in “the middle insula, superior parietal lobule, right periaqueductal gray, right globus pallidus (medial), right caudate nucleus (dorsal head), left ventral tegmental area and left rostro-dorsal anterior cingulate cortex.” This can be seen in the figure below:

Regions showing stronger activation during "unconditional love" condition

So what are the interpretations of these results? Does it surprise you that both hypotheses were confirmed? First, that unconditioned love was related to reward structure activation was not surprising. But the researchers over-interpret the results: they claim that this is prima facie proof that unconditioned love is rewarding. But hey, the results can just as well suggest that the unconditioned love state is just a framing of how we look at faces (for example, imaging you are either told that person/face X is a wonderful person OR an evil sadistic terrorist).

Second, is it surprising that they also found “activation not found for maternal or romantic love”? Not to me: the tasks are different, the selection of subjects are different, the confounds are plenty…

And what about that strong and bilateral insula activation? Yes, it’s right that it confirms the second hypothesis…but how does the insula play a role in unconditioned love? As I noted in my previous post, it does seem to play an important role in negative emotions and aversion. Here, the authors assert:

There is increasing evidence that the insula is implicated in the representation of bodily states that colour conscious experiences (or “background feelings”) (…) it is plausible that the middle insular activation noted during the UL condition was associated with the somatic and visceral responses elicited by the presented pictures.

Uh yes, but this is typically reflected in negative emotions. So how is unconditioned love related to aversion? Or maybe one could relate the findings to a recent review that suggest a role for the insula in addiction and urges? I don’t know, if you’re into speculating, go with whatever seems to work… Basically, this handwaving interpretations is not much better than old-style phrenology or hand-reading. They may be right, but only because they make the right guesses from previous studies.

Briefly put, although we enjoy the quirky side of neuroscience, and how it can be used to explore human nature, we at BrainEthics are also sceptical at the level at which quirky science turns into flaky science.

-Thomas

Read Full Post »

I am one of the organizers of a three day conference on neuroaesthetics that takes place at the University of Copenhagen from September 24 to September 26. If you are interested in the relation between art and the brain please consider joining us for what I believe will be an exiting event.

I am one of the organizers of a three day conference on neuroaesthetics that takes place at the University of Copenhagen from September 24 to September 26. If you are interested in the relation between art and the brain please consider joining us for what I believe will be an exiting event. I am sure loads of you neuroscience buffs out there will be interested in hearing that a new book on neuroaesthetics has just been published. Edited by myself and Oshin Vartanian, it is published by Baywood. You can buy it

I am sure loads of you neuroscience buffs out there will be interested in hearing that a new book on neuroaesthetics has just been published. Edited by myself and Oshin Vartanian, it is published by Baywood. You can buy it  From time to time we bring you the quirky side of neuroscience here at BrainEthics. Now, we discover a funny little study in

From time to time we bring you the quirky side of neuroscience here at BrainEthics. Now, we discover a funny little study in